This morning I read a recent article by WashU Professor John Inazu1 about why he feels that much of the discussion of threats to religious liberty is overblown. While I personally enjoyed reading his article, I believe that he misses the point behind why many Americans feel like religious liberty is under threat, which is at the core of what Hugh Hewitt was seeking to address in the article that Professor Inazu was responding to. While one can point out that Hewitt’s comments were hyperbolic (which they were), as US History is replete with examples of either secular bigotry against religion, or one religious group discriminating against another, or some combination thereof2, and that political rhetoric is usually overheated, I do think that Hewitt has a point concerning the intensifying attacks on religious liberty in the public square. Therefore, in this article, I seek to lay out why I believe that Hewitt has a point about religious liberty in the present, even if the rhetoric that he uses is hyperbolic.

De Jure and De Facto

First of all, in Professor Inazu’s article, there is not enough distinction paid to the difference between de jure (what the law says) and de facto (the on-the-ground situation) in the debates over the protection of religious liberty. This is a very important distinction, as we shall discuss, as the constitutional law and the popular culture are in stark contrast on these matters. Furthermore, this distinction shows how people can, in good faith, disagree as to whether or not religious liberty in under threat. After all, one can point out that recent religious liberty cases have usually gone in the direction of religious liberty, and connected issues such as that of school vouchers for parochial schools, appear to be going in a positive direction for religious liberty. At the same time, people can point to parts of the culture and various actions of the administrative state that are increasingly anti-religious and make the opposite point.

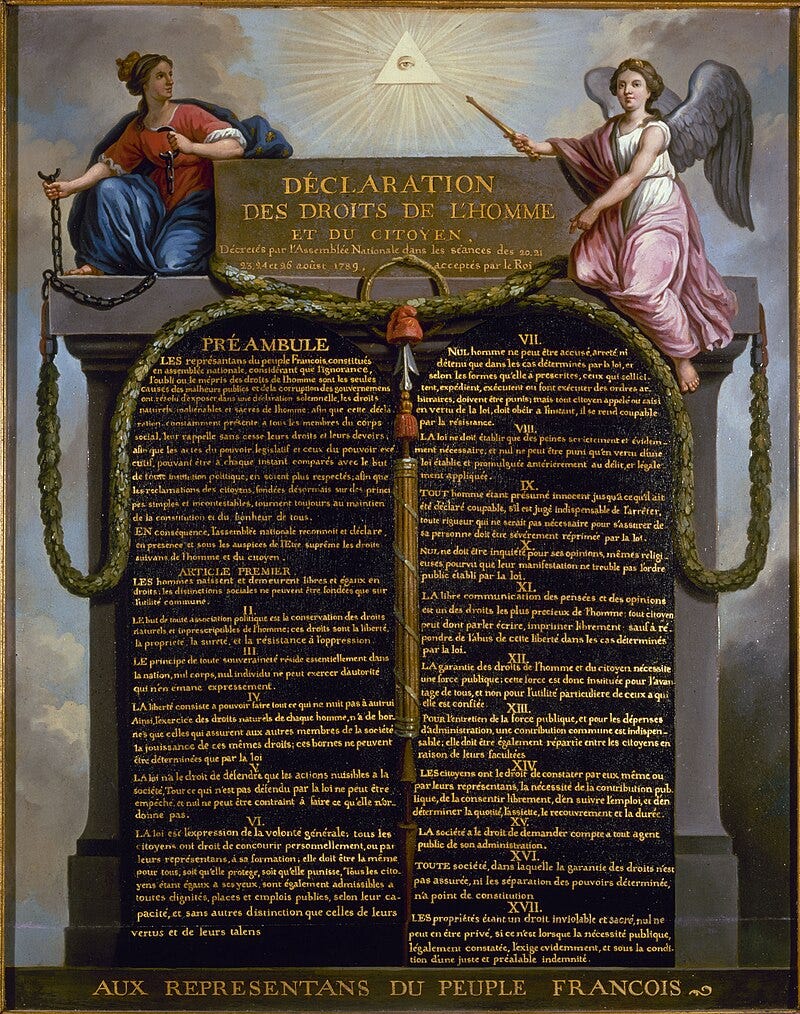

I would personally argue that the de facto on this matters a lot more than the de jure. To take some extreme examples, the First French Republic, the Second Spanish Republic, and the USSR all had religious liberty on paper but were extremely active in the violent persecution of Christianity on behalf of their totalitarian ideologies. This is not to compare contemporary America with any of these states but to point out that the existence of something on paper means is objectively an incomplete way of determining what that society values or does not. The reason why the 1st Amendment protects religious liberty (and Article 124 of the Soviet Constitution did not) is not due to the text itself, but instead due to the overall culture and feeling towards religious liberty in the United States. By contrast to the USSR, some states have been very de jure anti-religious, but de facto deeply religious, as shown in Guillaume Cuchet’s research on the depth of Catholic practice until the 1960s in France3, which showed that French secularism was not due to the Third Republic’s de jure 1905 Separation of Church and State (as is commonly believed), but instead due de facto cultural change caused by the abandonment of certain Church practices in the 1960s. As articulated by Joseph de Maistre in his Essay on the Generative Principle of Political Constitutions, an actual constitution is, definitionally, merely a summary of the culture and attitudes of a people, and whatever words are written down onto a written constitution are thus inconsequential. Likewise, religious liberty in the United States has less to do with the legal opinions of members of the Supreme Court than it has to do with it. One can look at how frequently the Supreme Court has reversed itself on its view of religion in the First Amendment to see that no number of cases, precedents, or interpretations of the First Amendment (or even the text of the First Amendment itself) are enough to protect religious liberty. Instead, the protection of religious liberty is reliant on the culture and morals of a people.

As America increasingly substitutes Christianity for therapeutic individualism and moralistic therapeutic deism, it is easy to see how toleration of traditional religious beliefs will be increasingly threatened, first culturally and then legally. It is impossible to miss things such as the social ostracization of Christian belief and practice, particularly concerning where traditional Christianity contradicts the values of modernity. It is not hard to imagine that holding to traditional Christian beliefs on contraception, divorce, abortion, etc can be enough to prevent one from anything from being appointed as a judge to earning tenure, to even getting a job. Indeed, the goal of the secular culture seems to be to try to push as hard as it can on these issues, for example with the Obama administration’s “contraception mandate”(which due to the death of Scalia was never struck down). Even cases such as Masterpiece Cakeshop seem like pyrrhic victories for religious liberty, as the same baker is being sued again for a slightly different infraction against the liberal culture. Furthermore, there are an increasing number of cases that use “anti-discrimination law” to infringe on religious liberty, by making the expression of basic parts of Christian belief a fireable offense. Though it might be illegal to fire someone for (for example), holding to the Nicene Creed, post-Bostok, it also can be a legal imperative (in some jurisdictions) for an employer to fire an employee for holding to the implications of the Nicene Creed on any number of issues, lest the employer be sued. Therefore, one can see that the de facto antipathy towards certain Christian beliefs is increasingly seeping into the legal culture, even cases argued on religious liberty grounds are usually settled in favor of religious liberty.

Across the Pond

The other thing that shows how religious liberty is under threat in the present, despite its de jure protections in the US, is how it is under threat both de jure and de facto in Europe. While an obvious example comes to mind in the continuous and unrelenting case against Päivi Räsänen, a Finnish politician on trial for stating her opinion on marriage, there are countless others. In the UK, the European country most similar to us in political and legal culture, one can be arrested for silently praying outside an abortion clinic. Likewise, a teacher can be fired by a Church of England-run school for agreeing with the Church of England on sex and gender. Across the channel in France, the state is trying to forcibly disband an association of Catholic schools under church supervision. European parents also lack the same civil rights that American ones do concerning homeschooling. European laws on “hate speech” also seem not to cover hate against Christians, as shown by the ECHR declaring the interruption of Christian religious service and desecration of an altar to be covered by free speech, while simultaneously banning the burning of the Koran. In Canada, it has also become routine for Christian Churches to be burnt down in acts of arson caused by spurious claims made by the Trudeau government.

These European examples are directly relevant to the American context insofar as the European Union and the United States share, for better or for worse, a single political culture and many Atlanticist institutions (such as NATO), and largely have the same ruling class. Increasingly American discourse on many issues has sept into European discourse, especially concerning cultural issues, much to the dismay of many Europeans, especially in Central/Eastern Europe (where there are long histories of colonization by either the West or Russia/USSR), who view this Americanized discourse on issues of sex and gender to be “ideological colonization.” Thus, the EU can be viewed as an incubator for many of the ideas of the transatlantic ruling class. While Americans cannot blame Brussels directly for much of this, though Europeans can, our State Department often acts in lock-step with Brussels and undermines American interests by supporting various ideologies that are at odds with religious liberty.

Current Threats to Religious Liberty in the US

As these European examples may still seem distant, it is worthwhile to point out that there are increasing voices that are calling for similar laws against religious practice in the US. The best example of this is the call by Beto O’Rourke to strip religious institutions (including churches) of their tax-exempt status if they dissent from the popular culture on certain matters. This call was, quite frankly, shocking to me when it was made (I was watching the debate where he made it), but was largely overlooked and not discussed, which suggests that it was not controversial and indeed a normal view for his audience (the viewers of the Democratic debate where he made it). At the same time, the administrative state has increasingly shown itself to be hostile to religious belief and traditional religious believers, such as with the infamous memo that accused Catholics of being some form of violent threat, which ridiculously cast Catholic pro-life activism as on par with various violent nativist groups. Furthermore, the administrative state, especially the DOJ, routinely goes out of its way to target pro-life activists and those who seek to apply their faith to their civic engagement. Furthermore, the DOJ has also put out documents that have accused parents (both Christian and non-Christian) who oppose pornographic books in schools, as being some form of potential terrorists or extremists. Thus, it is clear that the administrative state is openly hostile to religious liberty and the practice of religion.

Furthermore, there are already laws on the books in the US that allow the prosecution of religiously minded protests. The most notable of these is the FACE Act, which was recently used to (unsuccessfully) prosecute a pro-life activist over an altercation involving his son and a pro-abortion protestor. The FACE act is even more draconian than that would suggest, as it allows, and has been used in the past to, prosecute pro-life protestors for blocking the entrance to abortion clinics. That it exists and has not been struck down for violating either the right to protest or on religious liberty grounds is objectively absurd. Similarly, administrative rules and regulations are oftentimes used in such a way as to penalize religious institutions. While I have already brought up the Obamacare contraception mandate, there are other notable examples, such as Title IX regulations being used to try to enforce liberal views on gender in universities (and thus conservative/religious colleges such as Hillsdale, University of Dallas, or Christendom do not accept federal funds).

The Limits of Religious Liberty

Lastly, it can be argued that the current debate about “religious liberty” is far too limited in its scope as it purely covers religious beliefs and not philosophical beliefs that may or may not be downstream from religion. In this sense, religious liberty protections are somewhat counterproductive as they create a box within which religion can exist, but aligned ideas from a not explicitly religious standpoint are disallowed. For example, on the salient issues of marriage, sex, and gender, one can hold to traditional Christian beliefs without being Christian. For example, some of the strongest arguments on these topics come from non-Christians or cultural-Christians, such as Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution or Mary Harrington’s Feminism Against Progress4. Likewise, as historians such as Tom Holland have demonstrated, in his book Dominion, much of what we (in the West) consider to be objective morality we only know because of Christianity, and thus even Secularism is (to an extent) made possible because of Christian morality. This is even ignoring the “transcendental argument for God,” which is predicated upon morality and natural law, as well as the whole school of neo-Kantian deistic supporters of natural law, such as Kelsen, who believed in natural law without believing in Christianity. While I disagree with Kelsen and neo-Kantianism, and I believe that any attempt to preserve Christian morality and natural law without Christianity is ultimately doomed (as natural law is true because Christianity is true, not vice-versa), the fact that these views would not be covered by “religious liberty protections” shows how shallow such protections are. One should not have to derive specific philosophical or moral beliefs directly from one’s religion for them to be viewed as valid and protected by society. This shows one of the two biggest pitfalls in the religious liberty debate, that many people are irreligious but have moral opinions that are indirectly derived from religion, and the current protections do not protect the views of these people.

Furthermore, “secularism” is merely a chimera on which new pseudo-religions are allowed to take hold, while traditional religion is penalized and forced into the box of “religious liberty protections” and out of the public square. Man is naturally religious, there is no such thing as an irreligious man, and man will always worship at one altar or another, be it the true one of Christianity or the false ones of ideology, materialism, or any other number of things. Therefore, what is put into and out of the box of “religion” by jurists is rather arbitrary. Why can, for example, gender ideology be taught in schools while “religion” cannot, even if the former makes what are objectively bolder metaphysical and anthropological claims than the latter? Indeed, the claims of gender ideology, such as the belief that everyone has a “secret sacred self” that can exist contrary to physical reality and that people can transform their sex simply by thinking differently, are objectively religious. Therefore, why is it that (for example) prayer in schools or the study of scripture in schools is disallowed, while the study of gender ideology is all but mandatory in large parts of the country under the guise of “sex-ed?” In short, “religious liberty protections” merely tell religious believers that their beliefs are tolerated so long as they only exist within a box, while the pseudo-religious ideologies of the present are allowed to run amok in society.

Conclusion

While I understand what Professor Inazu is saying in his article, and Hewitt was indeed likely being hyperbolic, we should avoid viewing the protections on religious liberty as either adequate or tenable. Similarly, the government and overall culture are not exactly balanced in the way that they see religion when compared to various ostensibly secular ideologies. Thus, I think that there is very great cause for concern when it comes to the future of religious liberty issues over the next decade and beyond. This brings me to my final point, which addresses Professor Inazu’s argument about the outcome of religious liberty cases at the Supreme Court over the past decade. These cases have oftentimes been decided along partisan lines at the Supreme Court, and thus for such protections to be continually upheld, the ideological balance of the Supreme Court must be maintained. As even cases as clear-cut and obvious, as Masterpiece Cakeshop were only decided by a partisan margin (in that case 5-4), it is easy to surmise that if, for example, “Madam President” had gotten “her turn” in 2016 or if Al Gore had succeeded in his election denial in 2000, then we would have a de jure position more akin to that of Europe. Furthermore, if the current attempts at delegitimizing the Supreme Court as “Ultra-MAGA” and “extreme” are successful and court-packing becomes a possibility (or if the same rhetoric incites violence against a conservative member of the Supreme Court, which it arguably has already), then it is likely that we will get a bench that is outright hostile to religious liberty. As demonstrated by Carl Trueman (in his discussion of Lawrence v. Texas), those in favor of liberal individualism at the expense of traditionally held beliefs about the human person, do not care about how many precedents they must overturn to get their way. This makes it so that de jure religious liberty is thus largely dependent on the composition of the Supreme Court, while de facto religious liberty is reliant on the increasingly anti-Christian popular culture. One need not agree with Hewitt’s hyperbolic rhetoric to see that he makes a very strong case.

Who I have not met, but has always been kind and generous in emails

Usually, religious discrimination or discriminatory policy in the US has not been done in the name of any type of religious conservatism/traditionalism, but instead in the name of some form of secular deism. For example, the anti-Catholic “Blaine Amendments” cast themselves as being in defense of the separation of church and state. Likewise, the state persecution of Confessional Lutherans during World War I oftentimes cast the Lutherans as public enemies for wanting their own schools and for being opposed to the secular “social gospel.” The most extreme example of this religious bigotry on behalf of secularism was the support by the US Government of the socialist and state-atheist regime of Plutarco Calles during the Cristero War. During this conflict, various anti-Catholic hate groups, such as the rabidly racist and nativist Ku-Klux-Klan raised money for the Calles in the name of defending secularism.

On an unrelated note, in my view, Cuchet’s research is some of the most important to ever have been done on the sociology of religious practice. Here is a link to an English-language article about his work.

If I recall correctly, both women have converted to Christianity since writing their books, and similar to Ayaan Hirsi Ali, they became convinced of the claims of Christianity through an appreciation of Christianity as a civilizational and moral force.